But it was Sparsh a year earlier that actually placed her on a firm footing. It was never properly released as its producer Basu Bhattacharya (a filmmaker of considerable renown) in all his wisdom, decided to put it in cold storage. A pity, as it finds Naseeruddin Shah at his career’s best as a blind man who can see the world trying to smother him in sympathy and won’t have any of it.

What makes Sai Paranjpye’s Sparsh such a special film about a specially-abled character is Anirudh’s (Naseer) stubborn refusal to be slotted as a victim. So dogged is Anirudh in circumventing sympathy and even empathy from those around him that he ends up practising a reverse kind of disability-oriented isolation where the victim appears to want so desperately to appear ‘normal’ and so anxious to belong to the mainstream of society that he ends up making those around him feel acutely conscious of how to not allow the specially-abled person to feel disabled for even a second.

Throughout the delicately threaded film we see Naseeruddin Shah not looking blind at all. The National Award for Best Actor that he received for Sparsh was a meager reward for what is arguably the best portrayal of a blind person and his inner-world in the history of world cinema. And I include such universally-acknowledged portrayals of the sightless as Audrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark, Rani Mukherji in Black, Kimura Tatsuya in Love & Honor and Joren Seldeslachts in Blind.

Naseer surpasses all these timeless portrayals of the sightless. His performance is far superior to the film. Sai’s film seems to have suffered from a lack of budget. But it makes up for the rough edges with its unaccented message on humanism. Some of the scenes with the children at the blind school are truly heartwarming. At one point when Shabana Azmi buys a candle off a blind boy whose friend is shown to be teasing him about his unsold creation, the overwhelmed boy reciprocates her kindness by saying, ‘Didi, your saree is lovely.’

Trivia On Sparsh:

Filmmaker Basu Bhattacharya, producer of Sparsh, who for reasons best known to him, didn’t want to release the film. For 3 years it was in the cans. Finally Shabana Azmi and Sai Paranjpye undertook a vocal public protest against the creative smothering. That’s when the film was released.

The film was actually shot in a blind school. And Naseeruddin Shah’s character was based on the principal of the blind school.

Om Puri who made a grand breakthrough with Aakrosh the same year that Sparsh was released, had a cameo part in Sparsh.

The Sarod maestro Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, then only in his 20s, made a guest appearance playing at a public concert.

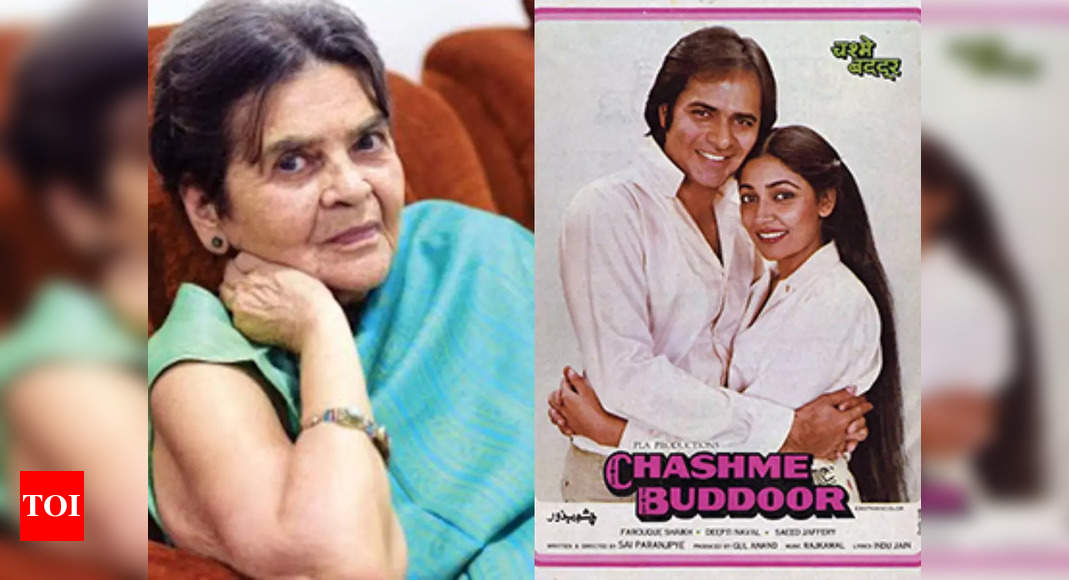

After Sparsh Sai Paranjpye made a number of notable films, like Chashme Buddoor (1981) and its “spiritual sequel” Katha (1983), Disha (1990) and the atrociously bad Saaz (1997) where she cannibalized and dramatized the lives of the Mangeshkar sisters to create a pulp ‘friction’. Watch Sparsh again, and you will forgive Sai all her trespasses.

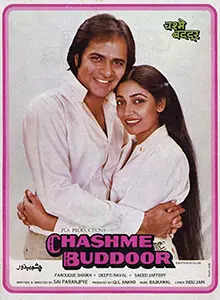

Chashme Buddoor (1981) was Sai Paranjpye’s achingly sweet rom-com that harks back to the era of innocence when college students chased girls all across town hoping to get them to agree to a coffee or a movie. Sex, if at all, was never discussed. The gently clever plot of Sai’s film could be divided into three movements. In the first movement Rakesh Bedi and Ravi Baswani playing despicably deceptive pals to the relatively sober Farooq Shaikh, cook up an elaborate fantasy romance with the girl next-door Deepti Naval. In the second movement the devilish duo tries to mess up Shaikh’s romance with Deepti. And in the third and final movement Bedi and Baswani desperately try to reconcile the lovers.

The narrative is strewn with a warm bonhomie that suggests a sense of equilibrium in the universe even when human intentions are far from legitimate or sensible. What works wonderfully for Sai Paranjpye’s game-plan are the credible actors, each embracing his or her character with the conviction of permanent ownership.

Farooq and Deepti are as convincing as a couple as any two strangers who decide to forge a relationship probably because they haven’t met too many potential soul-mates to choose from. Baswani and Bedi’s roguishness bolsters the plot’s action forward into a logical finale.

Incredibly the Farooq-Baswani-Bedi trio smokes all through the film. There is hardly a frame where one or all three are not seen puffing away at the cancer stick. Perhaps this is a sign of those relatively innocent times when youngsters smoked because they thought they looked cool doing so.

While most of the episodes still hold up with edifying momentum some of what seemed cleverly innovative 30 years now seems only to be self-indulgent. There’s an elaborate song in a park where Farooq and Deepti wonder how couples in films manage to sing loudly in public places. Then they proceed to do the same to the accompaniment of sniggers from onlookers.

Offbeat or middle-of-the-road filmmakers always demonstrated a discomfort with conventions of mainstream cinema. Were they just genuinely disdainful of the potboiler or cloaking in snobbery their inability to cope with conventional ingredients? In Chashme Buddoor Sai Paranjpye ably straddles the two worlds of a superior intellectual projection of cinematic conventions and mass entertainment. See the film for its cute and still-fresh take on love and courtship.

And yes, there is a cameo by the Big B and Rekha where he courts the girl by pretending to have found her handkerchief. This was 1980s. No one could escape the Bachchan trap. Not even Sai Paranjpye who made the art of ladki patana look decent. Even when the protagonists used cheesy pickup lines they were never offensive. A waiter is shown to become privy to Farooq’s courtship with Deepti. It’s the waiter who announces interval in the film. Characters in this film are allowed to be clever even at the cost of crossing the camera range.

It’s a world of cerebral satire where lovers avoid being filmy but don’t mind if their togetherness suggests an affinity with screen couples who woo one another with songs and peotry. Chashme Buddoor is world freed of pain. Though the characters inhabit the middle-income group they are untouched by suffering. No one dies in Chashme Buddoor. Not even while laughing. There are no ‘LOL’ moment in Sai’s scheme of humour. We smile because the sound of loud laughter doesn’t suit this film’s purposes. Easy does it.

Sai Paranjpye is rightly celebrated for Chashme Buddoor which set a new benchmark for burlesque and banter, and also gave Farouq Sheikh and Deepti Naval an opportunity to display their comic timing. But Sai was far more confident with her laugh lines in Katha(1983), a risible re-telling of the tortoise and hare fable with Farooq and Naseer playing against each other with remarkable ease and fluency. Deepti Naval was the chawl chick with a big flower in her oiled hair whom both actors wanted to win. What a pleasure to see Farooq cast as the wicked wheelerdealer. Sai named him Basu Bhatt after filmmaker Basu Bhattacharya who didn’t allow one of her best films, Sparsh to release.

Trivia on Katha:

Film critic and filmmaker Khalid Mohamed re-made Sai Paranjpye’s Katha. The remake which Khalid described as his homage to Sai, produced by Anjum Rizvi, featured Maniesh Paul, Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub and debutante Sharmiela Mandre. It never got released. Unlike David Dhawan’s remake of Chashme Buddoor, Khalid’s Katha had Sai’s approval.